International Women’s Day 2024: What can we learn from Elizabeth Denby?

Every year, the world celebrates International Women’s Day on 8 March. For 2024, the UN is celebrating it under the theme ‘Invest in women: Accelerate progress’. The UN writes that in the last 4 years, 75 million people have been pushed into severe poverty. They attribute this to economic downturn, climate change, the COVID pandemic and geopolitical conflicts. For this year’s International Women’s Day, the UN are calling for nations across the world to invest in women, to ensure that gender equity can be achieved for the benefit of society.

With this in mind, it’s interesting to consider how this plays out following the announcement of the Budget on Wednesday 6 March. The plans laid out for Britain by the Chancellor had the veneer of investing in women and

society, but unfortunately will only worsen the lives of those who are already struggling. While the housing crisis affects those of all genders, women also have to jump through various hoops due to gender discrimination and other gender-related issues such as domestic violence. The number of people who have been pushed into homelessness and are now living in Temporary Accommodation have skyrocketed. Women now constitute 60% of the total number of those in TA, and 1 in 38 lone mothers are homeless. Rough sleeping in England has increased by 27% in the last year, with women making up 15% of rough sleepers altogether – this is a 22% increase since the previous year. Every eight minutes, a family is hit by a Section 21 no-fault eviction. Moreover, adding domestic violence into the equation means that women are often forced to choose between staying in an unsafe situation and making themselves (and potentially their children) homeless.

These sobering figures are a stark contrast to where Jeremy Hunt’s priorities lay, considering the cut to Capital Gains Tax (CGT). By slashing CGT, this could prompt more landlords to sell up and puts more renters at risk of eviction and homelessness. It shows a lack of intent in solving this housing crisis in the long-term, and needlessly puts millions in precarious situations.

What we need is investment into housing if we want to accelerate progress. At Advice for Renters, we believe that a good life starts with good and affordable housing, and this encompasses more than just Maslow’s basic physiological need for shelter. That’s why we also believe that there is plenty to learn from social reformer Elizabeth Denby’s contributions to the housing sector.

Elizabeth Denby was an inter-war era social housing expert and consultant who advocated for the building of more social homes. After gaining her degree from the London School of Economics in social studies, she was motivated to draw the Government’s attention to resolve the problems she witnessed from her job in the voluntary housing sector in the 1920s. This included major overcrowding, which caused issues for not only on the people living in such conditions, but also for the local authorities. Denby played a critical role in the organisation of a series of exhibitions for the Kensington Housing Association between 1931 and 1938 to raise awareness about the slum problem across London.

In 1936, Denby drew on these lived experiences of people who were rehoused in subsidised housing built after the First World War to give her lecture to the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA). She was the first ever woman to do so and used this platform to criticise the inaccessibility of the homes provided to her interviewees. There was a lack of lifts and sound insulation, “inefficient and inconveniently placed equipment”; the homes were just not built for families.

Instead, she proposed in her speech that housing should be informed by these “slum-dwellers’” experiences. She advocated for the creation of more social housing. These developments should be considered in areas closer to their places of work, but also have “provision for recreation, for health, for fun”. Her ideas were considered polarising at the time but seem so common sense to us today.

She brought her ideas to life through her collaboration with the renowned architect Edwin Maxwell Fry from 1934-1937.

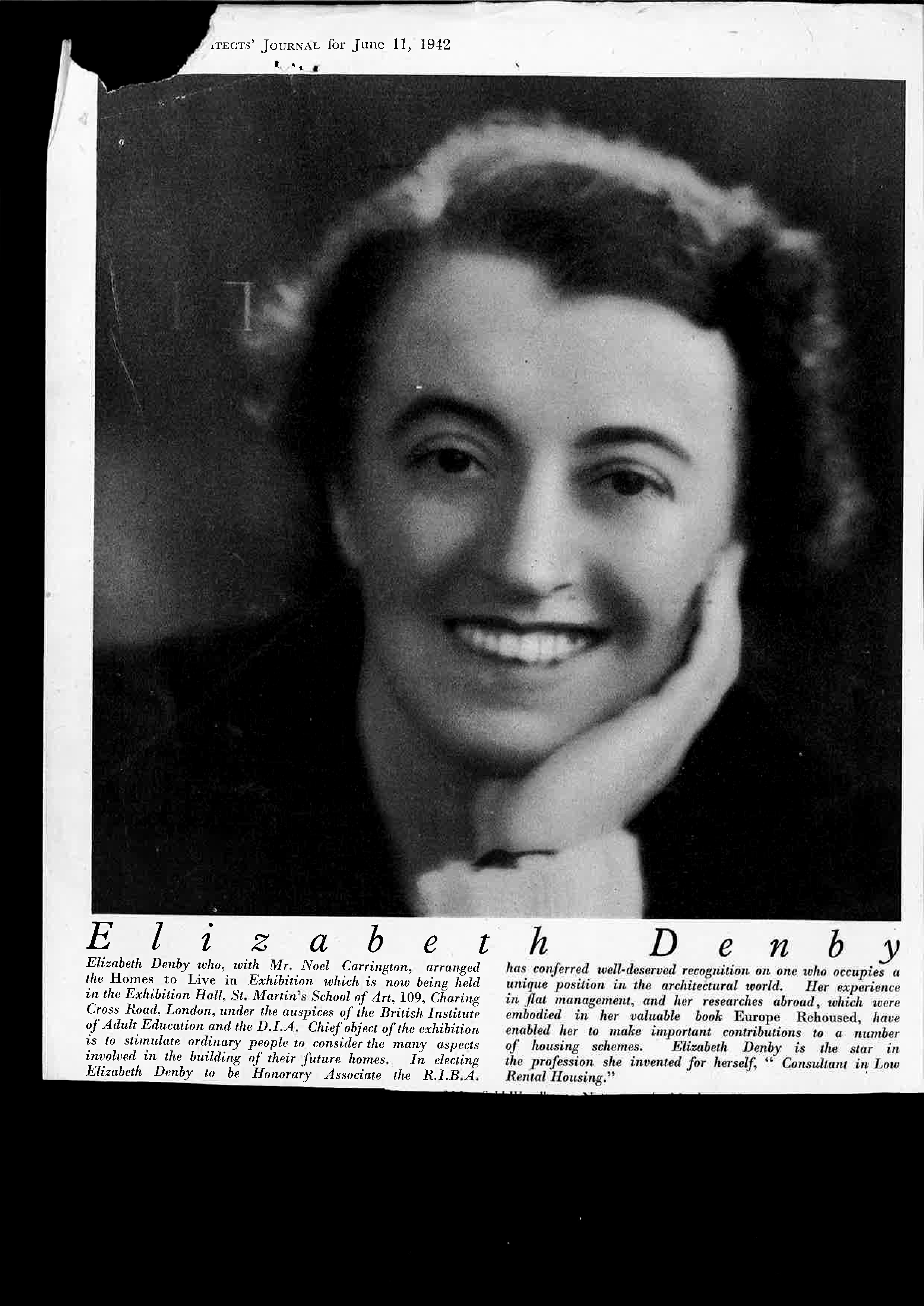

Photo credit: https://www.architectsjournal.co.uk/news/role-models-elizabeth-denby-and-marjory-allen

Both Kensal House in Ladbroke Grove and Sassoon House in Peckham were borne out of the scheme completed by Denby and Fry, with Denby then working as an independent housing consultant. These two blocks of social housing in London were her revolutionary contribution to the modernist social housing world; they both emphasised the value she placed on not only accessible and affordable accommodation, but also access to social amenities.

In these photographs of Kensal House below, we can see a school right next to the flats, with their “drying balconies” and large windows. There were also two social clubs in Kensal House, one for adults and one for children. Allotments were also available for tenant use and were run by a tenant-led committee. Trees were planted around the estate, giving residents many shaded areas and green space. Due to the close proximity of all the amenities, Denby described it as “the first urban village to be built in Britain”. The way that Kensal House was constructed was conducive to the creation of a small community within this block of flats. Denby herself resided on the new estate as she continued her consulting work, noting that she saw the residents mingling with one another “leaning elbows on the rail, smoking, gossiping, happy, like a group of cottagers”.

Photo credit:

(1) https://www.ribapix.com/Kensal-House-Kensal-Rise-London-the-circular-nursery-school-and-playground_RIBA15808?ribasearch=aHR0cHM6Ly93d3cucmliYXBpeC5jb20vc2VhcmNoP2Fkdj1mYWxzZSZjaWQ9MCZtaWQ9MCZ2aWQ9MCZxPWVsaXphYmV0aCUyMGRlbmJ5JnNpZD1mYWxzZSZpc2M9dHJ1ZSZvcmRlckJ5PTAmcGFnZW51bWJlcj0y

(2) https://architectuul.com/architecture/kensal-house

(3) https://rbkclocalstudies.wordpress.com/2015/12/03/better-living-through-gas-kensal-house/

Sassoon House, shown below, was also built to “transform the lives and environments of at least some of London’s urban poor”. Like Kensal House, its south London counterpart also offered families who lived there a sense of community and accessible amenities, as well as a home that was affordable, spacious, and well-furnished. It was the best environment for a family to thrive.

During this time, she was also conducting research for her book ‘Europe Unhoused’, where she travelled around various European countries such as Denmark, Finland, Hungary, and Czechoslovakia. This publication was her treatise on the various housing systems across Europe, and she found that Austria, particularly Vienna, had the most ‘complete’ model. It recognised that “shelter is not enough, that human beings needed companionship and recreation, need beauty in environment, need the help that can be given to parents still in slums by taking their children into nurseries”. She also commended Sweden’s model of tenant-led co-ops was also beneficial to building social stability. But most of all, she found that housewives’ experiences and needs were ignored by most of Europe, despite them being the ones who spent most of their time in the domestic realm.

So, what can we learn from Elizabeth Denby?

We cannot normalise the effects of this housing crisis. It’s due time that our politicians embrace these imaginative ideas already laid out by those who came before us and those around us. They need to look at housing from the perspective of those who are on the frontlines of this housing emergency, so that their thinking around housing can stretch beyond the limits of what economic benefits it may bring to our country. Listening to and investing in women will provide benefits for the rest of society; this must include investing in affordable and accessible social housing that not only will offer shelter, but also community and the resources needed for them to flourish.

For further reading:

Darling, E. (1999) ‘Elizabeth Denby, Housing Consultant: Social Reform and Cultural Politics in the Inter-War Period,’ https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/10066631/1/Darling_Elizabeth%20Denby_thesis.pdf

Denby, E. (2015) ‘Europe Rehoused,’ https://books.bk.tudelft.nl/press/catalog/download/708/818/742-1?inline=1

Froud, D. (2015) ‘Role models: Elizabeth Denby and Marjory Allen,’ https://www.architectsjournal.co.uk/news/role-models-elizabeth-denby-and-marjory-allen